Cancer starts when cells in the body start to grow out of control. Cells in nearly any part of the body can become cancer and can expansion.

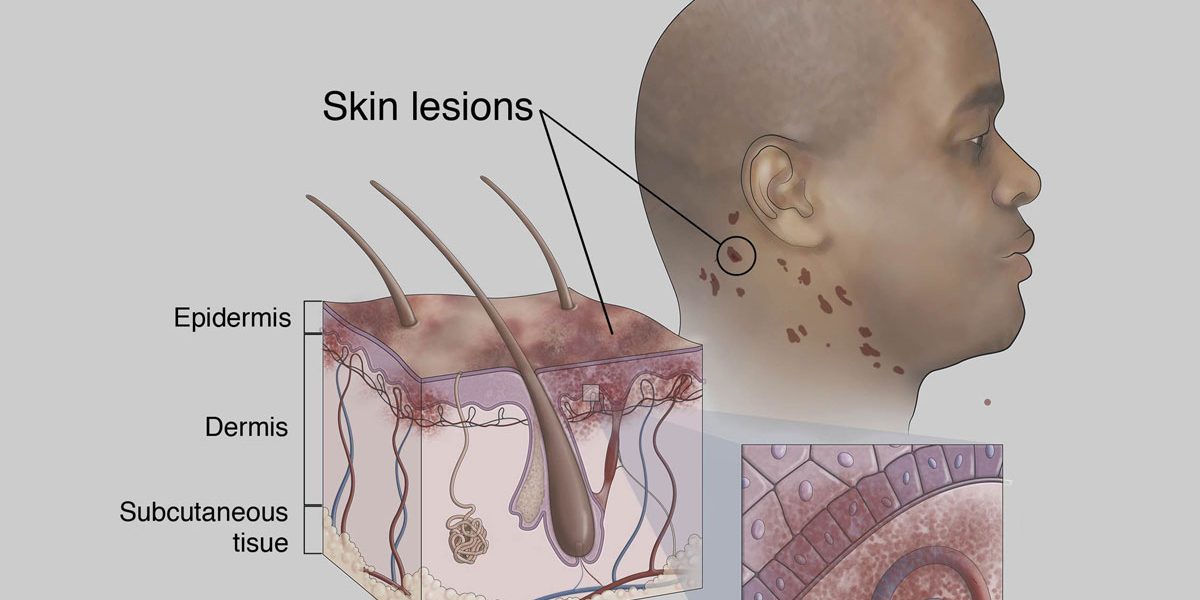

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a cancer that spread from the cells that line lymph or blood vessels. It usually appears as tumors on the skin or mucosal surfaces such as inside the mouth, but these tumors can also spread in other parts of the body, such as in the lymph nodes (bean-sized collections of immune cells throughout the body), the lungs, or digestive tract.

The abnormal cells of KS form purple, red, or brown blotches or tumors on the skin. These affected areas are called lesions. The skin lesions of KS most often show on the legs or face. Some lesions on the legs or in the groin area may cause the legs and feet to swell painfully.

KS can cause serious problems or even become life-threatening when the lesions are in the lungs, liver, or digestive tract. KS in the digestive tract, for example, can cause bleeding, while tumors in the lungs may cause trouble breathing.

There are four different types of KS defined by the different populations it develops in, but the changes within the KS cells are very similar.

Epidemic (AIDS-associated) Kaposi sarcoma

The most common type of KS in the United States is epidemicor AIDS-associatedKS. This type of KS develops in people who are infected with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS.

HIV stands for human immunodeficiency virus. A person infected with HIV (someone who is HIV-positive) does not necessarily have AIDS, but the virus can be present in the body for a long time, often many years, before causing major illness. The disease known as AIDS begins when the virus has seriously damaged a person’s immune system, which means they can get certain types of infections (such as Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus, KSHV) or other medical complications, including KS.

KS is considered an AIDS defining illness. This means that when KS occurs in someone infected with HIV, that person officially has AIDS (and is not just HIV-positive).

In the United States, treating HIV infection with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has resulted in fewer cases of AIDS-associated KS. Still, some patients can develop KS in the first few months of HAART treatment.

For most patients with HIV, HAART can often keep advanced KS from developing. Still, KS can occur in people whose HIV is well controlled with HAART. Even if KS develops, it is still important to continue HAART.

In areas of the world where it is not easy to get HAART, KS in AIDS patients can advance quickly.

Classic (Mediterranean) Kaposi sarcoma

Classic KS occurs mainly in older people of Mediterranean, Eastern European, and Middle Eastern heritage. Classic KS is more common in men than in women. People typically have one or more lesions on the legs, ankles, or the soles of their feet. Compared to other types of KS, the lesions in this type do not grow as quickly, and new lesions do not develop as often. The immune system of people with classic KS is not as weak as it is in those who have epidemic KS, but it may be weaker than normal. Getting older can naturally weaken the immune system a little. When this occurs, people who already have a KSHV (Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus) infection are more likely to develop KS.

Endemic (African) Kaposi sarcoma

Endemic KS occurs in people living in Equatorial Africa and is sometimes called African KS. Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus (KSHV) infection is much more common in Africa than in other parts of the world, so the risk of KS is higher. Other factors in Africa that weaken the immune system (such as malaria, other chronic infections, and malnutrition) also probably contribute to the development of KS, since the disease affects a broader group of people that includes children and women. Endemic KS tends to occur in younger people (usually under age 40). Rarely a more aggressive form of endemic KS is seen in children before puberty. This type usually affects lymph nodes and other organs and can progress quickly.

Endemic KS used to be the most common type of KS in Africa. Then, as AIDS became more common in Africa, the epidemic type became more common.

Iatrogenic (transplant-related) Kaposi sarcoma

When KS develops in people whose immune systems have been suppressed after an organ transplant, it is called iatrogenic, or transplant-related KS. Most transplant patients need to take drugs to keep their immune system from rejecting (attacking) the new organ. But by weakening the body’s immune system, these drugs increase the chance that someone infected with KSHV (Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus) will develop KS. Stopping the immune-suppressing drugs or lowering their dose often makes KS lesions go away or get smaller.

Causes

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is caused by infection with a virus called the Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus (KSHV), also known as human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8). KSHV is in the same family as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), the virus that causes infectious mononucleosis (mono) and is linked to several types of cancer.

In KS, the cells that line blood and lymphatic vessels (called endothelial cells) are infected with KSHV. The virus brings genes into the cells that can cause the cells to divide too much and to live longer than they should. These same genes may cause the endothelial cells to form new blood vessels and may also increase the production of certain chemicals that cause inflammation. These types of changes may eventually turn them into cancer cells.

KSHV infection is much more common than KS. Most people infected with this virus do not get KS and many will never show any symptoms. Infection with KSHV is needed to cause KS, but in most cases infection with KSHV alone does not lead to KS. Most people who develop KS have the KSHV and also have a weakened immune system, due to HIV infection, organ transplant, being older, or some other factor.

The number of people infected with KSHV varies in different places around the world. In the United States, studies have found that less than 10% of people are infected with KSHV. The infection is more common in people infected with HIV than in the general population in the United States. KSHV infection is also more common in men who have sex with men than in men who only have sex with women.

In some areas of Africa, up to 80% of the population shows signs of KSHV infection. In these areas the virus seems to spread from mother to child. KSHV is also found in saliva, semen, and vaginal fluid, which may be some ways it is passed to others.

Treatment

For some people with Kaposi sarcoma (KS), treatment may remove or destroy the cancer. The end of treatment can be both stressful and exciting. You may be relieved to finish treatment, but it is hard not to worry about cancer coming back. This is a very real concern for those who have KS, since treatments often do not cure the disease.

For many people with KS, the cancer never goes away completely. Some people may get regular treatments with chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or other therapies to try to help keep the cancer in check. Learning to live with cancer that does not go away can be difficult and very stressful. See Managing Cancer As a Chronic Illness for more about this.

Life after Kaposi sarcoma means returning to some familiar things and making some new choices.

Follow-up care

During and after treatment, it’s very important to go to all your follow-up appointments. During these visits, your doctors will ask about symptoms, examine you, and order blood tests or imaging studies such as CT scans or x-rays. Follow-up is needed to see if the cancer has come back, if more treatment is needed, and to check for any side effects. This is the time for you to talk to your cancer care team about any changes or problems you notice and any questions or concerns you have.

Almost any cancer treatment can have side effects. Some last for a few weeks to several months, but others can be permanent. Don’t hesitate to tell your cancer care team about any symptoms or side effects that bother you so they can help you manage them.

Ask your doctor for a survivorship care plan

Talk with your doctor about developing a survivorship care plan for you. This plan might include:

- A suggested schedule for follow-up exams and tests

- A schedule for other tests you might need in the future, such as early detection (screening) tests for other types of cancer, or tests to look for long-term health effects from your cancer or its treatment

- A list of possible late- or long-term side effects from your treatment, including what to watch for and when you should contact your doctor

- Diet and physical activity suggestions

- Reminders to keep your appointments with your primary care provider (PCP), who will monitor your general health care

Keeping health insurance and copies of your medical records

Even after treatment, it’s very important to keep health insurance. Tests and doctor visits cost a lot, and even though no one wants to think about their cancer coming back, this could happen.

At some point after your cancer treatment, you might find yourself seeing a new doctor who doesn’t know about your medical history. It’s important to keep copies of your medical records to give your new doctor the details of your diagnosis and treatment. Learn more in Keeping Copies of Important Medical Records.

Can I lower my risk of Kaposi sarcoma progressing or coming back?

If you have (or have had) Kaposi sarcoma, you probably want to know if there are things you can do that might lower your risk of the cancer growing or coming back, such as exercising, eating a certain type of diet, or taking nutritional supplements. Unfortunately, it’s not yet clear if there are things you can do that will help.

Adopting healthy behaviors such as not smoking, eating well, getting regular physical activity, and staying at a healthy weight might help, but no one knows for sure. However, we do know that these types of changes can have positive effects on your health that can extend beyond your risk of Kaposi sarcoma or other cancers.

It is very important for people who have had Kaposi sarcoma to do what they can to keep their immune systems healthy and to limit their risk of infection. If you are HIV-positive, this means being sure to take your antiviral medicines regularly. Talk with your doctor about getting vaccines and other steps you can take to help prevent infections.

About dietary supplements

So far, no dietary supplements (including vitamins, minerals, and herbal products) have been shown to clearly help lower the risk of cancer progressing or coming back. This doesn’t mean that no supplements will help, but it’s important to know that none have been proven to do so.

Dietary supplements are not regulated like medicines in the United States – they do not have to be proven effective (or even safe) before being sold, although there are limits on what they’re allowed to claim they can do. If you’re thinking about taking any type of nutritional supplement, talk to your health care team. They can help you decide which ones you can use safely while avoiding those that might be harmful.

If the cancer comes back

If the cancer does recur at some point, your treatment options will depend on where the cancer is located, what treatments you’ve had before, and your health.

Getting emotional support

Some amount of feeling depressed, anxious, or worried is normal when KS is a part of your life. Some people are affected more than others. But everyone can benefit from help and support from other people, whether friends and family, religious groups, support groups, professional counselors, or others.

The list of some Kaposi Sarcoma medicine: